Still Moving was a multi-artform solo exhibition, presented at St Heliers Street Gallery, Abbotsford Convent in August 2016. This work was made over and between 2 sites: in the village of Marnay-sur-Seine in France, in and around the Abbotsford Convent, and on the flight in between the two countries. Read the essay which accompanied the work here.

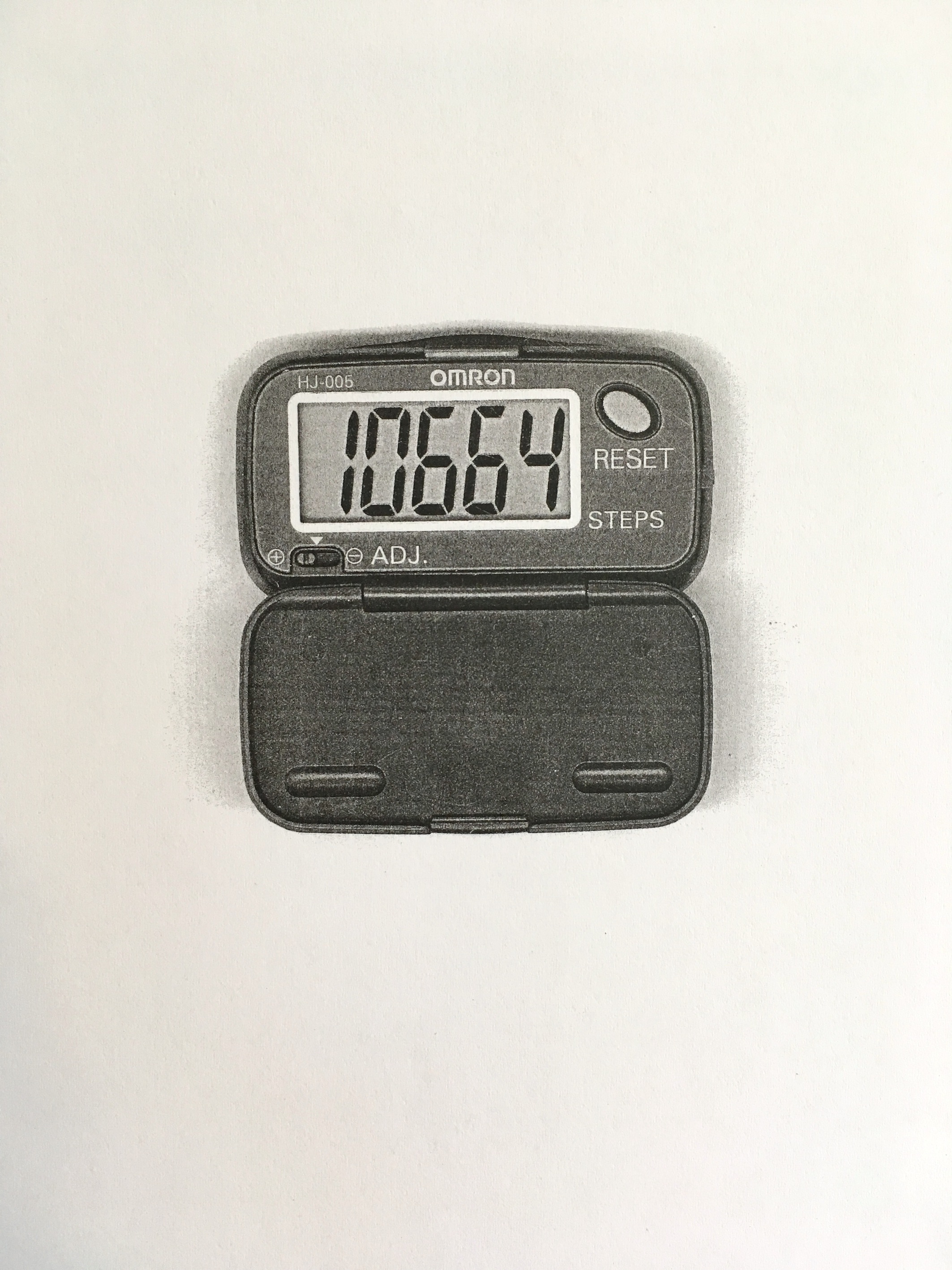

10,664:

the amount of steps taken from my house in Melbourne, Australia to arrive in Marnay-sur-Seine, France via aeroplane. On arrival in France, I commenced walking in the direction southeast, back to Melbourne, eventually arriving in the outskirts of the village Pont-sur-Seine after stepping 10,664 times.

Still Moving

Lizzy Sampson

While undertaking an arts residency in a small village in rural France in 2013, my collaborator Hervé Senot and I set out to gather moss from roofs around the village.

Alongside moss gathering, we cleared rocks from fields, and manually unflooded nearby paddocks and forest inundated by recent floodwater, bucket by bucket – returning the river back to itself.

Rather than remain in the studio, we sought tasks that would somehow be ‘useful’ to the village of Marnay-sur-Seine. We had traveled across continents to undertake small actions, focusing on elemental things – not actually knowing if we were assisting anyone or achieving anything by performing this ambiguous labour.

–

The proverb ‘A rolling stone gathers no moss’ is decidedly ambiguous. Unless we know the value of moss, how are we to know whether or not it is something we wish to accumulate?

Through the act of gathering, we move out into the world – closely observe and seek out the conditions where moss grows. Walking and wandering, observing and following trails, looking closely to the ground for the minutiae of soft, green sponge.

And stillness is required for moss to grow.

‘At the scale of moss, walking through the woods as a six-foot human is a lot like flying over the continent at 32,000 feet. So far above the ground on our way to somewhere else, we run the risk of missing an entire realm, which lies at our feet. Mosses and other small beings issue an invitation to dwell for a time right at the limits of ordinary perception…’[1]

–

When taking flight across the world to France, I wondered how much physical effort I needed to exert to reach my destination? If I were to exert the same amount of energy on the ground, where would I end up?

I remember very little about the flight to France.

–

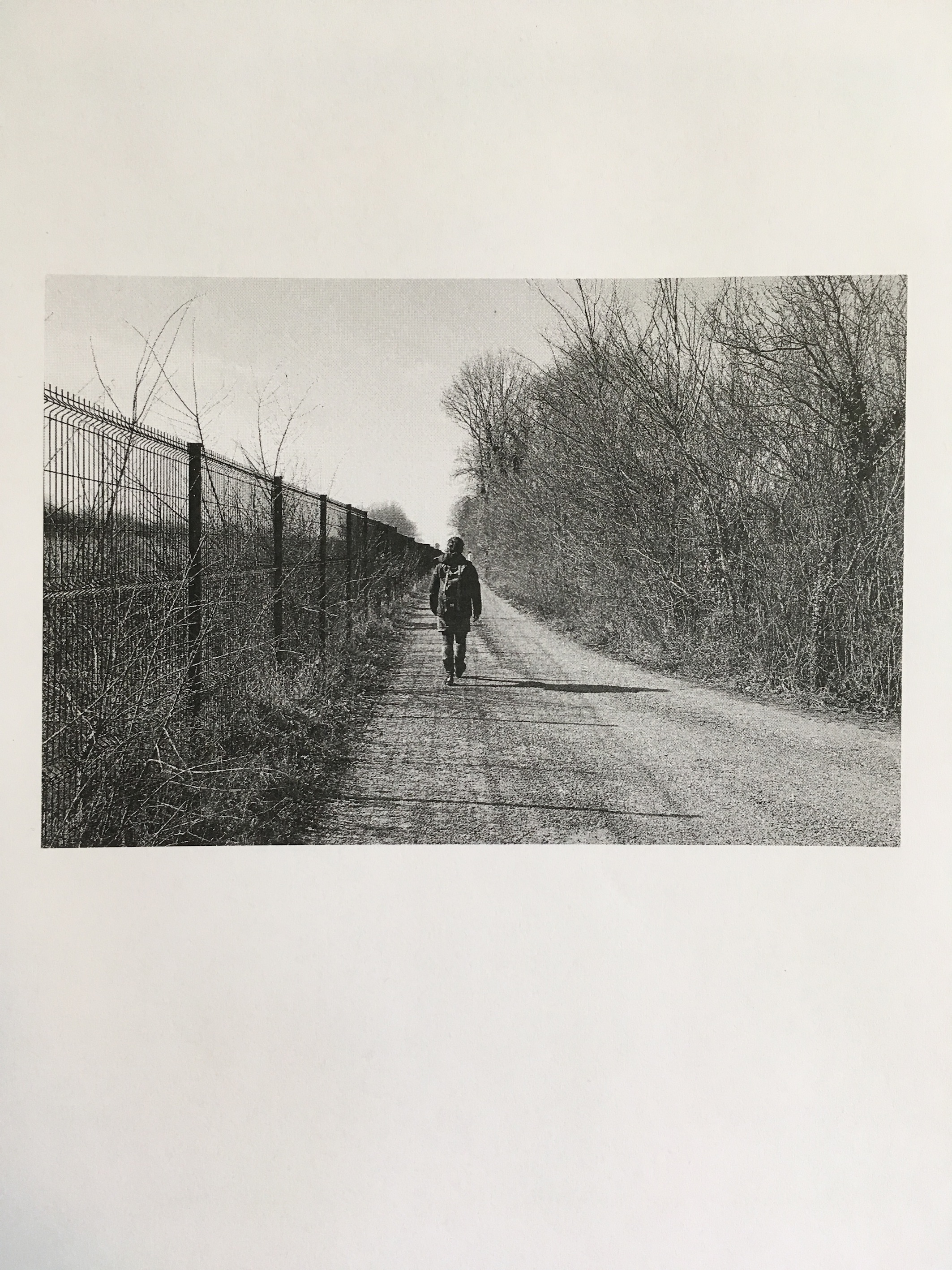

I remember every detail of the walk I undertook when I reached the old stone studio by the Seine river in France. Using my pedometer to count 10,664 steps (the amount I’d taken since leaving Melbourne and arriving in France – pacing the aisle of the aeroplane, queuing in the customs lines, walking from the taxi to the terminal…), I walked in a southeasterly direction heading for Melbourne.

I encountered abandoned houses, savage barking dogs, ankle deep mud, deer in the distance. I walked along a stretch of highway, a canal, briefly encountered the river and wandered through the narrow streets of Marnay-sur-Seine. Each detail seemed heightened in anticipation of wandering with a parameter. Walking… is already – within the speed culture of our time – a kind of resistance[2] says Francis Alys. My walk felt significant – a counter to the global flying phenomenon, where I would find comfort in small details and unknown destinations.

And ‘while industrial means of transport threaten to make our limbs and our senses obsolete, walking persists in defining human life as a matter of territorial and political activity.[3]

On the flight from Melbourne to Paris, we crossed 21 major rivers – bookended by the Yarra and the Seine – I saw little of them.

–

The most common form of moss Bryum Argenteum spreads its spores across the world, sending them traveling in the air above us like ‘aerial plankton’. However, the more common route for dispersal is by footsteps.[4]

–

While wandering along the banks of the Yarra from the Convent back in the direction of France – again using counted steps as a creative constraint, I came across a monument to the Deep Rock swimming pool, located inconspicuously under a tree about 100 meters from the river bank. Marked on the monument is a reminder that the river bend used to extend further up the slope, to the very site of the plaque I was reading.

In 1970, the Yarra River was relocated to make way for the Eastern Freeway. Yarra Bend was reduced in size and moved south around 100meters.

Aerial imagery from 1945[5] shows Yarra Bend as it was before the freeway. Comparing this image to the river we see today shows the stark removal of the sharp ‘U’ bend, and speaks of the dispossession of the cartographies of colonisation and the price of progress.

I return via foot with an image of the river. Standing under the noise of the freeway traffic, looking up at the lights of the freeway trying to disguise themselves amongst the trees, I reflect on the quietness and stillness, which is forever missing from this reduced bend.

–

In 2013, the Seine river burst its banks and flooded the fields of Monsieur Maillet so that his cows could not graze on the land and had to be relocated. Like the Daughters of Danaus, who were condemned to spend eternity carrying water in a sieve, the act of bucketing floodwater back into the river turned out to be a futile action of sorts, but this is what we did for 3 days in Marnay-sur-Seine.

–

‘With the current and against it

Don’t know where you’re rowing to

Is it backwards is it forwards

Is it forwards is it backward’[6]

By performing seemingly inconsequential acts – bucketing water back into the river, rowing against the current so as to stay in the same place, gathering moss or staring out the window across the riverbank to the birch forest – painting – little advancement is made.

Instead of making progress, something else is made. It is not in the outcome of the tasks we set out to ‘achieve’ where actions find their meanings. These actions and parameters become a mode of engaging with the local – participating in the particulars of a place while revealing our relationship to them.

–

The work in Still Moving began with reflections on taking flight – traveling across the world to remain in one place for an amount of time.

CAMAC arts centre where I spent a month collaborating with Hervé Senot presented many similarities to the Abbotsford Convent; a window looking to the River, an old stone building full of isolated art studios, a past life still present.

While the work and actions undertaken at CAMAC were an attempt to visualise and reflect on effort and energy – physicality, labour– the results after a month revealed a desire to find our ‘raison d’être’ within the place we resided for that time.

Rocks, Moss, Rivers – these still and moving elements have become the materiality on which to focus on back at the convent.

By walking around the peripheries of the convent site, I notice the bluestone which originated just 5000 steps away along the banks of the Merri in Clifton Hill, the moss growing under the leaky drainpipe – and the River, hidden from view but only meters away – all constants – for now.

[1] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses, Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, 2003, pp. 10

[2] Alys, Francis, Interview: Russell Ferguson in conversation with Francis Alys, Phaidon, pg31

[3] Medina, Cuauhtemoc, Fable Power, Francis Alys, Phaidon, pg 77

[4] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses, Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, 2003, pp. 93, 94

[5] http://1945.melbourne

[6] Refrain of Francis Alys work ‘Song for Lupita’

List of Works: